Carla Laureano is a bit of a Renaissance Woman. She has held many

jobs—including professional marketer, small-business consultant, and

martial arts instructor. Recently, she has added “published author” to

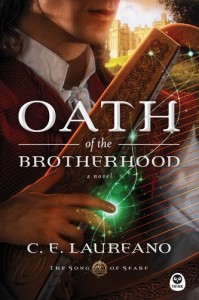

her repertoire. Her first novel, Five Days in Skye, was recently chosen as a double-finalist in the RWA’s 2014 RITA Awards. Oath of the Brotherhood

marks her fantasy debut. Carla graciously took some time to chat about

her writing career, YA fiction, theology in storytelling, and the

possible future of Christian publishing.

Carla Laureano is a bit of a Renaissance Woman. She has held many

jobs—including professional marketer, small-business consultant, and

martial arts instructor. Recently, she has added “published author” to

her repertoire. Her first novel, Five Days in Skye, was recently chosen as a double-finalist in the RWA’s 2014 RITA Awards. Oath of the Brotherhood

marks her fantasy debut. Carla graciously took some time to chat about

her writing career, YA fiction, theology in storytelling, and the

possible future of Christian publishing.

CARLA: It definitely wasn’t planned that way. My fantasy was out on submission, and given the difficulty in selling inspirational fantasy in this market, I didn’t want to start writing another epic speculative series. I took a few months to see if I could write a romance novel and discovered that not only was I capable of doing it, I enjoyed it. When ACFW time came around and I’d didn’t have any serious bites on the fantasy, I decided to pitch the romance. I came home with several requests for the full manuscript… and two days later found out that my fantasy was going to committee. I was then in the surreal position of having two contract offers almost simultaneously, and since the editorial calendars didn’t overlap, I accepted both.MIKE: There’s lots of “behind the scenes” things that happen to bring a book to publication – life issues, some sort of inspiration, a professional contact, a significant learning curve, etc. What are some of the most significant “behind the scenes” components that have led to your becoming a published author?

It’s hard to call myself strictly a fantasy author or a romance author, because I truly love writing both. (Naturally, I would pick the two most polarizing love-‘em-or-hate-‘em genres in which to write.) I’m not going to lie—writing two genres simultaneously is more than challenging—but they’re so different that switching back and forth gives my brain a rest and lets me appreciate the things that are unique to each genre.

CARLA: I’ve had some people comment on my “immediate success,” but in truth, I’ve been at this for almost twenty years. I wrote fantasy for the general market for years, coming close with agents a couple of times, but I was never able to sell a book. I finally realized that in trying to remove all spiritual components from my stories, I was hampering my natural voice. Once I decided to let the stories be told the way they were meant to be told, I started to find some interest in my work in the CBA. I went from being a finalist in the ACFW Genesis contest to having six books under contract in only two years. But that would never have happened if I hadn’t put in the work of learning my craft, submitting, and learning from my mistakes for nearly two decades.

MIKE: So Oath of the Brotherhood

is being marketed as YA. I’ve long contended that YA is a bit of an

artificial construct. Because a significant swath of YA readers are

adults, in some ways, labeling a book YA is a tactic to get adults and

young adults to read it. In your opinion, what distinguishes YA fiction

from adult fiction? And do you agree that the label is kind of nebulous?

MIKE: So Oath of the Brotherhood

is being marketed as YA. I’ve long contended that YA is a bit of an

artificial construct. Because a significant swath of YA readers are

adults, in some ways, labeling a book YA is a tactic to get adults and

young adults to read it. In your opinion, what distinguishes YA fiction

from adult fiction? And do you agree that the label is kind of nebulous?CARLA: In some genres, like romance or mystery, I think the label is necessary. There tends to be a pretty big content divide between YA and adult in those types of fiction. But with regard to speculative fiction, I do agree that the YA label can be a little nebulous. It’s the nature of speculative fiction to deal with bigger issues that would appeal to both teens and adults. Add the fact that the bildungsroman has always been a favored vehicle for telling speculative stories, and the gap between them narrows even further.MIKE: One Christian author, in writing about the limits of speculative fiction, recently suggested that zombies should be out of bounds for Christian fiction. Unless the fictional cause of zombie-ism is viral, there is no biblical precedent for the soulless dead returning to life. Of course, theology is important to a Christian writer. But how much theology do you think a Christian should impose upon their fiction? Should ANYTHING be fictionally out of bounds?

That said, there are some specific differences between YA and adult in terms of storytelling approach that I’ve only recently identified for myself. Generally, YA takes one or perhaps two characters and filters the bigger plot through their point(s) of view. If adult speculative uses a wide-angle lens, YA takes a zoom approach. There’s also typically a stronger and more integrated romance thread that’s integral to the story, whereas in most adult speculative fiction the love story could be removed without too much damage to the overall plot. Additionally, YA tends to handle the issues of sex and violence with more delicacy and less detail than adult fiction.

So from that perspective, YA is very much its own genre. I think it’s more helpful to ask what it is about YA that draws in adults. What appeals to me is the visceral nature of a close-in approach to storytelling. It’s almost as if literature tells us when we graduate from YA to adult books, “It’s time to grow up now. Trade all feeling for logic, and toss out the idealism while you’re at it.” But the issues dealt with in YA still resonate with people of all ages: identity, the need for acceptance and belonging, feeling of helplessness in a world that is simultaneously too big and too small. There’s also a sense of hope in most YA speculative fiction that we lack in our more cynical adult fiction, the idea that the world is worth saving and that a single person can make a difference. Even in The Hunger Games, which I think we can agree takes a pretty dim view of human nature, the reader gets the sense that it’s meant as a cautionary tale—and by extension, that we must take action now if we are to avoid this horrible end.

CARLA: I’m of the opinion that nothing should be imposed on a story that isn’t already there. I think that’s part of the complaint many people have with Christian fiction, that the religious aspect can feel tacked on or forced. Even a highly religious book in which the theology or the moral message is integral to the storyline or characters development will not feel preachy. But just like you can’t just decide to set a novel in space and call it science fiction, you can’t throw in a church scene and a conversion scene and call it Christian. It has to be organic to make sense.MIKE: I have been fairly critical of Christian fiction, its readers, and the strictures that govern it. It’s tilted predominantly toward women and women’s titles, the stories tend to avoid more edgy subject matter, and follow a traditional redemptive arc. What are your feelings about the current Christian fiction industry? Are you hopeful or skeptical?

That said, I’m quite conscious of the theology that I’m putting forward in my writing, both out of an understanding of the market and a sense of personal responsibility. If I put a Christian-like religion in a speculative setting and then through my story or characters imply that Christ is not the path to salvation, am I responsible for those who might be led away from the central tenet of our faith by those ideas? Possibly.

But does that mean that every book I write has to have an overt parallel to Christianity? No. And I don’t even think I have to have any recognizable religion in a book for it to have a Christian worldview. (It just might be a little harder to sell in the CBA.) I’m in an interesting position myself. Because the conflict between paganism and Christianity was a central one in the Celtic world upon which I based my setting, Oath of the Brotherhood has a pretty strong Christian slant. The other stories I’m developing have a much lighter spiritual thread. Will those books find a home with a traditional publisher? Only time will tell.

CARLA: I’m not sure I have a good answer on this. Most days, I think we’re headed in the right direction. We’re seeing edgier titles (though mostly in the women’s fiction/romance arena), and I know of a handful of new speculative projects that have been contracted by Christian publishers in the last few months. Not to say that I think the books out there now should not be published—it would be egotistical to argue that others’ reading tastes are less valid than my own. But I am encouraged that we may see a wider variety of titles, genres, and subject matter in the coming years. It will be interesting to see if the continuing buyouts of Christian publishers by the Big Five result in more choices or fewer choices in Christian fiction.

What checks my optimism on the subject is the immediate backlash against the publication of Matthew Vines’ God and the Gay Christian by Convergent Books, a sister imprint of Waterbrook Press under Penguin Random House. Despite the fact that Convergent and Waterbrook have completely different editorial missions, some people immediately called for a boycott of Waterbrook as well. If decisions made by a progressive imprint can harm a press that is related only by business structure, I wonder if conservative publishers will compensate by moving in the opposite direction and becoming even more cautious in their acquisitions.

You can find out more about Carla and connect with her at her website, on Facebook, Twitter, Google+, and Pinterest

0 comments:

Post a Comment

Don't be shy. Share what's on your mind.